Resource

Concentrated

Poverty

Rethinking the impact of economic segregation on student success

What is concentrated poverty?

You don’t need to work in education policy to know that family wealth and educational attainment are deeply linked.

But the relationship between poverty and student success is more complex than it might appear at first glance.

To really understand that relationship, it’s crucial to consider concentrated poverty — the frequent phenomenon where students from low-income backgrounds are clustered together in schools and school districts, which are drawn — and can be changed — by politicians.

For decades, research into the correlation between low student achievement and poverty focused primarily on students' individual socioeconomic factors.

Modern research, though, tells a more complete and complex story, revealing that student achievement of low-income students has as much to do with schools as with individual circumstances. This research reinforces that students’ financial situation does not predestine them to academic failure, and it serves as an urgent call to create economically integrated public schools.

"Our education leaders can’t solve poverty alone. The good news is: They don’t have to.

But they do have to stop concentrating all the students experiencing poverty into a few schools.”

— Ary Amerikaner, Brown’s Promise Co-Founder and Executive Director

An explanation of concentrated poverty from our Director of Policy and Advocacy

Revisiting old assumptions

In 1966, the first of its kind Coleman report introduced the idea of a Black-white student “achievement gap” and shaped the understanding of student achievement in America for decades to come.

The report examined data on schools, teachers, and students, concluding that disparities in family income and wealth, not school factors, mostly explained the achievement gap between Black and white students.

While many researchers, educators, and policymakers have questioned that conclusion over the years, the Coleman report has played an outsized role in shaping policy.

An updated perspective on the role of schools

In 2010, the Schools and Inequality report analyzed the same data from the Coleman Report and applied a more sophisticated method called hierarchical linear modeling (HLM).

This model found that, while family background does matter, school composition matters even more. That is, student success depends not just on how much money an individual student’s parents make but on the financial situations of all the students in the school.

Students from low-income families in schools with wealthier student bodies do much better than those in schools with high concentrations of poverty. In fact, the report found that “fully 40% of the differences in achievement” can be attributed to differences in schools—not students’ individual backgrounds.

“In dramatic contrast to previous analyses of the Coleman data, these findings reveal that school context effects dwarf the effects of family background.”

— Schools and Inequality report

As the authors conclude, “school context effects [including, specifically, socioeconomic and racial segregation of the school] dwarf the effects of family background.”

Poverty and education: A study of Maryland schools

A 2019 study from the University of Maryland also found that school-level poverty had a bigger impact on students’ success than individual poverty.

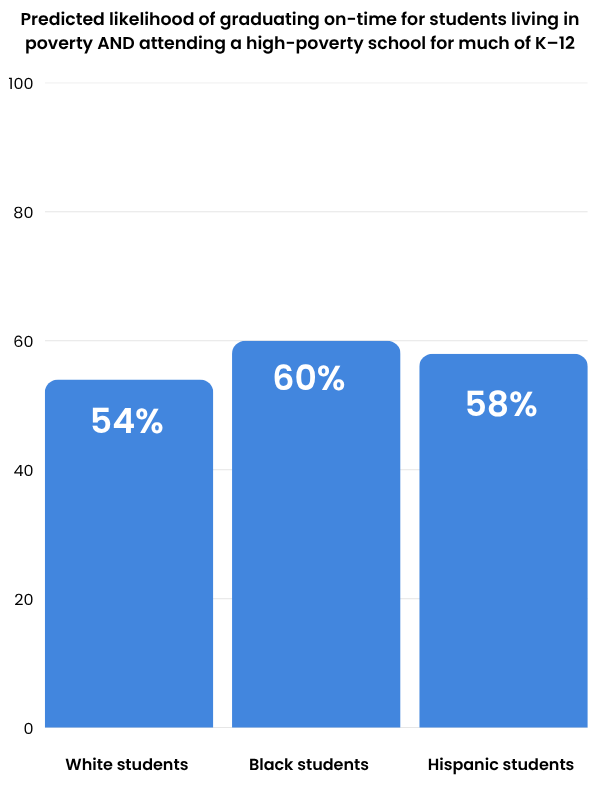

For example, the report predicted that, compared to a student from an average financial background in an average school, a Black, Hispanic, or white student living in poverty for much of their K-12 experience but generally attending schools without concentrated poverty was only about 6 percentage points less likely to graduate high school on time.

That same student who spends much of their K-12 years in a school with concentrated poverty was more than 30 percentage points less likely to graduate on time.

Living in poverty has a moderate effect on student graduation

Living in poverty AND attending a school with high poverty has a dramatic effect on student graduation

These findings demonstrate that reducing concentrated poverty in schools can dramatically improve educational outcomes and prove that a student’s socioeconomic background doesn’t seal their academic fate.

What does race have to do with it?

Going to a high poverty school is bad for all students, regardless of race or ethnicity. Across the country, due to systemic racism, children of color are both more likely to live in poverty than their white peers and also more likely to be assigned to a high poverty school.

In fact, most of the academic harms of racial school segregation can be explained by what researchers call “racial economic segregation,” which is the fact that racial segregation concentrates students of color in high poverty schools.

Student achievement factors in high-poverty schools

Why is concentrated poverty so damaging to student success? Before they ever set foot in a classroom, students living in neighborhoods with concentrated poverty face structural realities that negatively affect learning—from greater exposure to air pollution and trauma to reduced access to healthcare. So student bodies with high concentrations of poverty have increased needs at school. Yet research shows they consistently have less access to critical resources.

When Americans think about a lack of resources in higher-poverty schools, they likely picture outdated facilities and technology, both of which are real problems. But high-poverty schools also tend to lack equal access to less tangible resources. They frequently experience higher rates of teacher and leader turnover and, as a result, have fewer experienced teachers and school leaders. They are less likely to offer high-quality curricular materials or advanced coursework. And they are more likely to employ harsh, discriminatory disciplinary policies, just to name a few.

Explore our efforts

If we want to end educational inequity, we need to end racial and economic segregation in public schools.

Access to Integrated and well-resourced schools is not only a right promised by Brown v. Board, it is one of the keys to significantly improving student outcomes on a meaningful scale. We have the tools and the power to give every child in America the education they deserve.

Learn more about state policy solutions to end segregation →

Read next

What we can do

State Policy Solutions

We have identified five key policy solutions for state leaders. Progress in any one of these areas would help, but the best results will come from doing them all together.